International C2 Journal: Issues

Vol 1, No 1 (2007)

It’s an Endeavor, Not a Force

Background

Since the publication of the Tenets of Network Centric Warfare (NCW) in the NCW Report to Congress (DoD 2001), discussion of NCW, Network Centric Operations (NCO), Network Enabled Capabilities (NEC) and related concepts have begun with the assumption that a “robustly networked force” (Alberts et al. 1999, 82) is a crucial capability. However, the term force has also proven to be troublesome. Most readers, both in the military and civilian communities, understand the term to mean a military force. This has caused military institutions to focus on developing networks and capabilities that cover the military rather than the collection of entities required for success in the twenty-first century. In a similar fashion, civilians and other types of institutions have focused on developing their own networks.

Moreover, the term force implies direct actions that alter the operating environment because of their kinetic strength and impact, which is at odds with the need for effects based approaches to operations (synchronized efforts that employ the full range of instruments of national power and often involve nuanced actions and “soft power”) (Smith 2002, 110-111).

In addition, the term force implies a tightly coupled set of actors (individuals, groups, organizations, or institutions). However, we know that many of the collectives most important for protecting national security interests (across the range of military operations or ROMO), shaping the global security environment, and support to civilian authorities (disaster relief, humanitarian assistance, etc.) are composed of a wide variety of disparate actors (Joint U.S. military forces, military forces from coalition partners, international organizations [IO], Interagency partners from within the U.S. Government and from foreign governments, non-governmental organizations [NGO], government organized non-governmental organizations [GONGO], private voluntary organizations [PVO], private industry, local governmental authorities, traditional leadership [clans, tribes, etc.]) and public-private partnerships. Indeed, such groupings are seldom coherent, with underlying differences, sometimes profound differences, in their goals, structures, and processes. Calling these collections of actors a force is both incorrect and misleading.

Thesis

The argument presented here is that we should replace the term force with the term endeavor. As used here, an endeavor involves a large number of disparate entities whose activities are related to a broad range of effects, including not only (and very often not primarily) military, but also social, economic, political, and informational factors (Alberts and Hayes 2007, 9-11). The endeavor is made up of those entities that are cooperating (consciously or deliberately) in some particular context and those whose behavior is expected to aid those actors who have chosen to cooperate. This approach implies that actors within the endeavor may have a variety of different relationships with one another and may be working toward somewhat different goals or purposes. Indeed, their ability to work in concert may depend on the fact that their goals and objectives, while far from identical, are not mutually exclusive. The term endeavor also extends to include relationships with entities whose actions only incidentally support the goals of the endeavor. Such actors are less reliable partners than those who have chosen to work together, but they may nevertheless play useful roles under circumstances where their independently derived behaviors help create the conditions necessary for the success of the endeavor. The different types of relationships between the entities making up an endeavor are discussed in further detail below.

One crucial distinction between endeavors and other types of collectives is the set of dependencies and interdependencies involved in an endeavor. Endeavors are formed because no single actor within the collective is capable of achieving its relevant goals without appropriate activities and behaviors by others. Historically, this is why nations have formed alliances or coalitions during warfare. However, as the national security needs of nation states and the international community have broadened to include shaping the international environment to avoid overt conflicts and wars, cooperation between military organizations and law enforcement organizations to curb illegal activities (smuggling, pollution, illegal fishing, etc.), peace operations coupled with the need for economic, political, and social reconstruction, and support to civil authorities in humanitarian and disaster relief, the number and variety of entities with the necessary expertise, capabilities, and relevant social networks required for success has grown apace.

Organization of this Article

This article begins by exploring some historical examples of endeavors: U.S. efforts to interdict flows of illegal narcotics and other smuggling, the development of civil-military cooperation during crises and disaster relief, efforts to shape the global operating environment, and the conduct of effects based operations. Drawing on that broad set of experiences, it then develops ways of describing, measuring, and understanding endeavors, the different types of relationships between and among the parties to them, and the mechanisms needed to make them effective.

Countering Illicit Commerce

Over the past several decades the United States has continuously sought to stem the flow of illegal commerce over its borders. This has included efforts to prevent the flow of illegal narcotics (marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and amphetamines) into the country, to block or prevent the flow of illegal immigrants from around the globe, and to stop the importation of goods that infringe U.S. patent, trademark, and copyright laws. None of these efforts have been fully successful. However, they are excellent examples of the types of endeavors required to protect a nation state in the twenty-first century.

This discussion focuses on the efforts of the United States and its cooperating partners prior to September 11, 2001. After that date, the counter-drug mission was de-emphasized for many entities and many of the participating organizations were reorganized and their charters were revised. However, the several decades of less than successful efforts to halt illegal drug smuggling and consumption represent one of the largest and most serious endeavors available for analysis. Moreover, the fact that these efforts had only modest success reflects the reality that endeavors are created to deal with difficult challenges.

Historically, illegal drug smuggling was seen as an issue of border control. This made it primarily an issue for the U.S. Customs Bureau, which screened goods arriving through established Ports of Entry, whether they are airports, seaports, or along the land borders. The approaches by sea were the responsibility of the U.S. Coast Guard. The land borders between the Ports of Entry were the responsibility of the U.S. Border Patrol. However, drug smuggling was also carried out by individuals who were entering the country illegally and by gangs that sent members across the borders, so the Immigration and Naturalization Service became involved. Hence, the issue of illegal narcotics trafficking has long been an interagency issue.

Once inside the country, illegal drugs were also a domestic law enforcement problem. At the federal level, this initially involved the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the federal prosecutors around the country. State and local police and prosecutors were also involved because illegal drugs violated the laws they were responsible for enforcing. Police at all three levels found it necessary to find ways to work together, despite their very different organizational cultures. Because they were responsible for large areas of land that were often near the borders or were being used as landing or dump sites by smugglers as well as growing and storage areas, the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Reclamation, Department of the Interior (Indian Reservations), and the U.S. Park Service also became involved. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) became involved because the smugglers were importing and using illegal small arms. Recognizing the unique aspects of illicit drug smuggling and sales, the U.S. created a whole new federal law enforcement organization, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), to focus on the problem in 1973. Other specialized entities were created within these federal departments to focus on particular aspects of counter-narcotics (for example, to trace illegal money transfers FinCEN was created inside the Treasury Department). The Justice Department created Regional Information Sharing Systems (RISS) to handle counter-narcotics information across its organizations and the National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC) to bring information together for analysis.

Early in the counter-drug effort, the U.S. realized this was not wholly a domestic problem and began to seek international cooperation. This brought the Department of State into the mix. They focused initially on the direct border states of Canada and Mexico, but also came to work with a variety of governments where raw materials for illegal drugs were produced (e.g., Columbia and the Andean countries) or through which they transited (for example, Mexico, Venezuela, and the Caribbean island countries). Moreover, other governments with interests and resources in the transit zone including the United Kingdom (British Virgin Islands), France (Guadeloupe), and The Netherlands (Dutch Antilles) also became involved in seeking to stem this illegal trade. Over time, as the networks conveying these drugs spread across the globe, international institutions were developed to deal with the threat (such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission). As a natural consequence of these developments, INTERPOL became routinely involved.

The problem of illegal narcotics and their impact within the United States was also seen as a major national challenge, not only in terms reducing the supply, but also reducing demand. This spawned research into the effects of drugs on people and the economy (largely funded by the Federal Government), very large educational campaigns (both public and private) to prevent and reduce drug use, laws requiring drug testing for those engaged in public safety, transportation and other fields, searches for treatments that could cure addictions, and laws mandating sentences for those convicted of possession or trafficking in illegal drugs. Specialized NGOs and PVOs sprang up to help provide educational services and to deal with addicts. These trends increased when illegal narcotics came to be seen as one way AIDS was spreading within the country. Many private companies introduced pre-employment drug screening, employee support programs for those who developed addictions, and rules requiring drug tests after accidents or injuries. These efforts were encouraged and applauded by insurance companies. The medical community was tasked to report emergency room reports of patients suffering from overdoses or apparent drug poisoning. This involved both public and private hospitals and clinics. While all cooperating to deal with illegal narcotics and their impacts, deep rifts emerged between those who believed it was essential to disrupt the supply of drugs and those who believed first priority should go to reducing the demand for them.

As the size and variety of these efforts grew, Congress and the Nixon Administration declared a “War on Drugs” in 1971 (PBS). In 1988 Congress created the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) reporting directly to the President. This organization was tasked to coordinate the efforts of the country, including those in the private sector. Its director was recognized as the “Drug Czar” and received increased powers by President Clinton in 1993. During some periods of time the Director of ONDCP had significant input to the budgets of the agencies involved in the War on Drugs, but that authority was never strong (cabinet members could go around ONDCP directly to the White House to argue their cases) and not exercised very aggressively.

As the national level problem became even more widely recognized, the tasking of parts of the Intelligence Community and the Department of Defense (DoD) were altered to bring their assets to bear. This also made it routine for National Guard and Reserve forces to support the counter-drug mission in many areas. Specialized tactical analysis teams (TAT) were created, often within embassies abroad, to provide distributed capability wherever the need arose.

Involving the DoD and the Intelligence Community ensured that more assets were available, but also created some very real challenges, which were met by novel organizational arrangements. For example, while military and intelligence organizations were prepared and organized to generate and handle classified information, few of the other federal agencies involved had either cleared personnel or systems for handling that information. Moreover, the cost of vetting their personnel and creating the required control systems was considered prohibitive. Hence, new mechanisms for information distribution were developed and limited numbers of their personnel were processed for clearances. In many cases cooperation with foreign governments presented similar issues and work-arounds had to be found. Moreover, the Department of Defense cannot be used for law enforcement purposes within the United States and its territories except under extraordinary circumstances. Hence, specific arrangements were made that placed personnel with law enforcement authority aboard U.S. Navy ships to ensure the power of arrest was available when interdictions occurred in U.S. territorial waters.

Other novel organizational arrangements also developed, usually first as ad hoc responses to specific needs, then later as models to be emulated elsewhere. Two are particularly interesting: High-Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) and Joint Inter-Agency Task Forces (JIATF). Law enforcement and cooperating elements of the Intelligence Community and Department of Defense created interagency groups to concentrate on High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas so their resources and information could be closely coordinated under the leadership of DEA. Where DoD had the lead and was providing substantial resources (including facilities) Joint Interagency Task Forces (JIATF) were created, each with a different geographic focus.

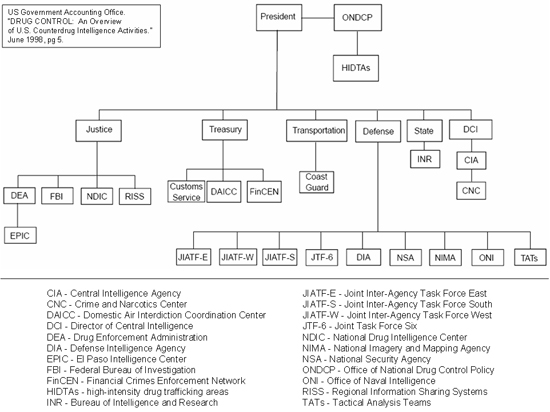

The resulting relationships within the U.S. Government are shown in Figure 1 as of 1998. This chart is greatly simplified, since each organization is shown in its formal reporting relationship, so the integrated efforts, such as JIATFs, are not connected to the several agencies that staffed them. Nor does it reflect the myriad Congressional committees with oversight and budgetary influence on the efforts. Moreover, it does not show linkages to the foreign governments cooperating in the endeavor except by noting the presence of the Department of State. Note that the only common “boss” for the U.S. federal effort was the President. Those familiar with Washington will immediately recognize the vast potential (too often realized) for bureaucratic infighting over turf and budgets inherent in such an organizational kludge. Moreover, the President had no direct control over state and local law enforcement, the non-federal medical community, or the host of NGO, PVO, and other entities involved in the effort.

FIGURE 1. U.S. Counterdrug Intelligence Operations, 1998

This lengthy example is important because it illustrates the number and variety of entities whose efforts must be focused in an endeavor, the fact that endeavors form to deal with large and complicated problems that no single entity can manage alone, the fact that endeavors require creating novel processes and structures, and that forming an endeavor is no guarantee of success.

Civil-Military Cooperation

The development of endeavors that require civil-military cooperation has been one of the most important enablers of effects based approaches to operations. During classic Industrial Age wars, such as World War II, a true “whole of government” approach evolved naturally and encompassed not only the civilian agencies of the government, but also private industry and a host of voluntary organizations. However, absent that type of dramatic need, the military tended to de-conflict its efforts from those of civilian agencies and the private sector. Exceptions were obvious and relatively rare—the need for military support during disaster relief or civil insurrection being obvious examples. However, after the end of the Cold War as the range of national security issues stretched the roles required of the military, greater interaction with civilians, both within and outside government, became appropriate. Moreover, many military missions today involve coalition forces either within established alliance frameworks (NATO, Korea, etc.) or in ad hoc coalitions formed for particular missions. Most missions (Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, etc.) include both military coalitions and civilian entities.

The militaries of the world have capabilities that are useful in a wide range of contexts, from disaster relief to security and reconstruction efforts. These include not only the instruments of coercive force but also portable communications, lift (air, water, and ground), and the capability to operate in austere environments, as well as organizational and planning skills and experience. Militaries also have some limited capability to provide police services, though only a fraction of their forces have the correct training and equipment to act in that capacity. They can also provide other services such as shelter, food, medicine, and potable water that may be important in many situations. However, civilian organizations (government agencies, IOs, PVOs, NGOs, GONGOs, and private entities) can also provide many of these services and are better suited to provide them on a long-term basis. Indeed, military organizations do not want to tie up their resources delivering such services for any longer than may be necessary. During reconstruction the skills of the civilian sector are often much more relevant as infrastructure, schools systems, health care, legal systems (including courts, prosecutors, and penal institutions), and economies are developed. Hence, it is in the interests of the military and the governments who deploy them to find ways to cooperate with civilians who are capable of taking on parts to the relevant burden.

International Civil-Military Cooperation

The topic of civil-military cooperation came into sharp relief for the United States shortly after the end of the Cold War when it became important to protect the Kurds in Northern Iraq. As it became clear that the military forces of Saddam Hussien were not going to be completely dismantled and that they were going to be used to subdue populations who were considered a threat to his regime, many Kurds fled into the mountains. The U.S. adopted security measures, including a no fly zone, to protect them.

However, this refugee population was at extreme risk because of the harsh weather conditions. The basic services they required (shelter, warm clothing, food, medical support, etc.) were initially provided through the military, but a variety of civilian organizations, particularly NGOs, came to play important roles. The military established Civil Military Operations Centers (CMOC) in order to coordinate these efforts. In many cases the NGOs and IOs needed lift to move their personnel and relief supplies into the mountains, as well as security at their delivery sites. At the same time, those organizations were able to provide professional, specialized services, which reduced the demands on the military forces.

While the CMOC approach was made to work well in Northern Iraq and began the long process of building trust and willingness to be interdependent in the military and NGO communities, it was roundly criticized by many outside the military. First, as implemented, CMOC was a military activity that took place “inside the wire” of military camps or bases. Secondly, the activities were dominated by the military, in no small part because they brought the bulk of the majority of the physical assets and planning effort. In many situations the NGO community also felt that merely being associated with the military threatened their perceived neutrality and therefore compromised their access and trust with the population. While this was a relatively minor factor in Northern Iraq, where the U.S. military was popular with the refugee population, this assumption would not hold in most peace or reconstruction operations. Hence, the idea of a Civil-Military Information Center (CIMIC) was born (and is still the preferred language of NATO and many countries today). While this language has grown to include the entire civil-military approach, it initially emerged as a location, outside the military bases or compounds, where civilian and military entities could exchange information and conduct coordination or collaborative planning. In many cases the military representatives shed their uniforms when attending these meetings. CIMIC locations were, however, typically resourced by the military because it had the physical assets required.

Over time, and as more and more civil military operations occurred, the NGO and IO communities recognized the value of having these centers and became adept at organizing them. Their version, typically termed a Humanitarian Operations Center or HOC, was led by a large NGO such as CARE or the Red Cross. These centers proved much more comfortable for the civilian communities because of the perception that they, not the military, were in charge. In many cases the military personnel attending meetings at a HOC wear civilian clothes. These centers are also more likely to work through collaboration, in no small measure because of the variety of very different organizations represented and the fact that they have highly focused functions and charters. In essence, HOCs rely on interdependencies. No single entity can deliver the services needed without the efforts of the others. This approach is particularly likely during disaster relief when security is a relatively minor issue.

The migration path for international civil-military cooperation has clearly been away from military-dominated structures and processes and toward coordination and collaboration efforts. Where the security situation is highly threatening the older approaches remain appropriate (and are probably the only feasible ways to operate). However, they tend to result in narrow coordination with both sides limiting information sharing. Hence, they are inherently less than ideal because the opportunities for synergy are quite limited. When circumstances permit, as in the tsunami relief effort or earthquake recovery in Pakistan, the more collaborative approaches are preferred, in no small part because they are more comfortable for the civilian partners, who are encouraged to undertake more of the burden.

In some senses, the coalition effort in Iraq during the period after defeating the armed forces of Saddam Hussein and before handing sovereignty over to a new Iraqi government was the worst of all possible situations. First, the security situation was perceived as very dangerous, which meant that NGOs and IOs either refused to participate or left as a result of their experience. For example, the UN cut back its presence dramatically once it was attacked. Secondly, because of U.S. perceptions of a need for rapid response and unitary leadership, the Department of Defense took the lead. This meant that the effort lacked many of the relevant skills available in State and USAID. Also, for bureaucratic reasons, severe limits were placed on the number and variety of experts from outside DoD who participated actively in the effort. Very few people were available who understood the Iraqi culture and too few native speakers and translators were available to support the effort. Finally, private companies were contracted to provide much of the technical work. Their tasking ranged from training Iraqi police and military units and providing security details for Coalition executives to undertaking reconstruction tasks (clearing garbage, providing potable water, opening schools, etc.) and supporting U.S. troops (long haul trucking, food service, etc.). The efforts of these companies were tied directly to their contractual obligations, which had the effect of imposing rigid hierarchies both in terms of tasking (chain of command) and function. All these factors came together to make agility and effects based operations very challenging (Ricks 2006).

At the same time, much greater success has been experienced in other environments. The responses to the Pacific tsunami and to the Pakistan earthquake are generally seen as sound endeavors in which a variety of actors (host governments, military organizations, NGO, PVO, International Organizations, and private industry) were able to find ways to work together. While these efforts took some time to form, partly because of the distances involved and the remoteness of the locations of some victims and partly because the participants had to meet “on the ground” and form their functional groupings “on the fly,” they proved largely effective. Even in relatively difficult security environments, such as East Timor and Afghanistan, relatively effective endeavors have been formed. As in the general history of endeavors, however, novel organizational arrangements have emerged. For example, in Afghanistan NATO has adopted a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) approach that is intended to bring together the relevant civilian and military capabilities needed in each area where it is operating. While the experience to date indicates that these teams are still dominated by their military components (which is a reflection of the security situation on the ground), this approach has the virtue of recognizing that the problems can only be solved by an endeavor that includes both civilian and military expertise and practitioners.

Domestic (U.S.) Civil-Military Cooperation

Civil-military cooperation within the United States has a long tradition and a number of well-established ground rules. National Guard units are the easiest to mobilize and use, with state governors as the key executives. Major events, such as hurricanes and floods, may result in federal support, which usually begins with nationalizing the National Guard (enabling it to get greater material support and work across state boundaries) and the local reserve forces from the Services. In extreme cases, and with Presidential approval, regular units from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps can be deployed.

Post September 11 and with the creation of Department of Homeland Security, plans for reacting to significant situations have been improved and a web of relationships and processes have been developed that are intended to facilitate the effective response of the Federal Government, including the Department of Defense. The National Response Plan lays out specific guidelines with respect to who has the lead in different types of crises and how local, area, state, and regional entities can both support one another and also request Federal assistance. Moreover, a number of exercises and demonstrations are conducted each year in an effort to ensure that everyone is aware of this plan and has the information, connectivity, and expertise to carry it out effectively.

However, despite the good intentions of everyone involved, the response to Hurricane Katrina demonstrated that the existing arrangements and processes leave a great deal to be desired. Many of the problems experienced were clearly a function of the scale of the disaster. However, more deeply rooted issues also emerged. Government entities at all levels tended to (a) worry about jurisdictional issues (rice bowls) even when they were clearly impediments to progress, (b) work in hierarchical chains of command, and (c) fail to distribute information broadly. Coordination of voluntary efforts proved clumsy and sometimes counter-productive as when qualified medical personnel were rejected because they had not been certified for disaster response emergencies, despite serious needs for their expertise and the availability of appropriately certified personnel to oversee medical efforts. Civil-military interfaces were sometimes confused as state governors sought to retain control over their National Guard units (in order to use them in law enforcement roles) while the Department of Defense sought to bring them into its larger planning efforts in other roles. Moreover, the delays inherent in following the National Response Plan, coupled with the losses of connectivity due to the flooding, made coherent planning and execution very difficult (White House 2006, 51-64).

Shaping the National Security Environment

While the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) and recent national strategy documents stress the importance of shaping the national security environment (DoD 2006), carrying out this mission has been a challenge for decades. Clearly an effective approach to shaping the environment is inherently an interagency endeavor. Its foci cut across initiatives aimed at specific countries, non-state actors, regions of the world, and global issues. They range from encouraging democracy and open economic systems to reducing poverty, avoiding failed states, providing effective assistance to refugee populations, and battling terrorism around the world.

The primary DoD entities involved in shaping the security environment are the Combatant Commands (COCOMs), particularly those with primary geographic areas of responsibility outside the United States: EUCOM, PACOM, SOUTHCOM, and CENTCOM. These COCOMs maintain programs that include a wide range of activities from port visits to military education and training and global issues such as counter-proliferation. They also provide the forces needed for humanitarian and disaster relief (e.g., Pacific tsunami and Pakistani earthquake), peace operations (e.g., Rwanda, Bosnia, Kosovo), as well as counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism (e.g., Philippines and Somalia). In addition, the COCOMs organize and support bi-lateral and multi-lateral exercises and are key resources for distributing military assistance to friendly governments. Over time, they also develop military-to-military ties with the armed forces from other countries, including many whose foreign and defense policies are not always aligned with those of the U.S. Some of the best insights the U.S. has into the capabilities and intentions of those governments, such as China, Indonesia, and former Soviet republics, come from military exchanges, workshops, and informal interactions.

However, the challenge of effectively and efficiently blending the efforts of DoD in general and the COCOMs in particular with those of other U.S. Government agencies involved in issues related to national security (obviously the Department of State and USAID in particular, but also departments such as Commence, Treasury, Energy, and Agriculture) has never been dealt with consistently or successfully. The U.S. Ambassador, as the direct representative of the President, is responsible for all U.S. Government activities in a foreign country unless extraordinary circumstances, such as a war, occur. Moreover, there are military personnel present in virtually all embassies wherever the Department of Defense has a significant presence or mission. However, the quality of interactions between the military and civilians in each country (as well as between the representatives of the other U.S. Government Departments active there) vary widely and appear to depend on personal relationships and trust. Given the very different organizational cultures present in these embassies and within the foreign countries at large, genuinely effective relationships are difficult to generate and maintain.

The nature of these differences as been thrown into sharp relief at this writing as DoD has announced the creation of AFRICOM (Africa Command), a new geographic COCOM to deal with that continent. Historically, EUCOM has had responsibility for that area of the world. However, a variety of factors have led to a perception that the Department of Defense should both increase its emphasis on Africa and also improve its focus and expertise. These include the successful attacks on U.S. embassies in Africa, the need to manage conflicts in the Horn of Africa, major refugee populations, the importance of Nigerian oil and the troubles within that country, the number of regional wars on the continent, and the concentration of failed states and potentially failing states there. Hence, this is a region where shaping is extremely important, as well as seen as much less expensive (in lives and treasure) than reacting to crises after the fact.

However, strong concerns about the impact of AFRICOM have been expressed by observers, particularly those with greater familiarity with the civilian sector. They point out that AFRICOM will have substantial material assets (primarily money, but also military trainers and equipment), which may dwarf the assets available through State, USAID, foreign governments, IOs, and NGOs. They note that DoD has been provided major funds for economic assistance programs worldwide as a result of the Global War on Terrorism, providing it with considerable leverage. Second, these critics are concerned that creating this military command will be seen as an indication that the U.S. is going to emphasize military approaches and solutions to problems and crises in the region, when the primary shaping activities needed are political and economic (Pincus 2007). These issues have not been ignored by DoD, which plans to have a State Department civilian as one of the two Deputy Commanders of AFRICOM and has issued a number of policy statements stressing the “soft power” approach and an emphasis on developing partnership capabilities. According to Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Ryan Henry, recent talks with six African nations have stressed the value of “the humanitarian, the building partnership capability, [and] civil affairs aspects” (Pincus 2007). Clearly, making AFRICOM a success will require a variety of endeavors that are effects based approaches to operations. The major ones currently underway in Africa, including the Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa established in 2002 and the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Initiative; each have unique sets of actors and focus on problems that cut across international borders and also depend on a variety of actors for success. Other potential missions in the region, such as peace operations and refugee relief in the DARFUR region, will also require working with a variety of different entities.

What is an Endeavor?

As noted earlier, an endeavor involves a number of disparate entities whose activities are related to a broad range of effects, including not only (and very often not primarily) military, but also social, economic, political, and informational factors.

| Put succinctly, complex endeavors are characterized by a large number of disparate entities that include not only various military units but also civil authorities, multinational and international organizations, non-governmental organizations, companies, and private volunteer organizations (Alberts and Hayes 2007, 9-10). |

The variety of entities involved includes, but is not limited to, joint and combined military organizations, interagency partners, international organizations, non-governmental organizations (whether independent of governments or supported by them), private voluntary organizations, local authorities, traditional leaders, private industry, and public-private partnerships. Endeavors form in order to deal with significant challenges or problems that no one entity believes it can deal with on its own. They are inherently disparate because the range of effects needed requires a variety of different approaches, types of expertise, and resources.

One crucial distinction between endeavors and other types of collectives is that the actors involved in an endeavor do not have a single leader or commander. If those entities share an effective “boss” they belong to an organization, not an endeavor. At least in theory, such organizations can have unity of command and unity of purpose (or closely shared purposes, which only emerge as a result of negotiation and collaboration in an endeavor). Endeavors do not always (or often) have the luxuries of clear chains of command or a completely shared purpose. Instead, they are made up of independent (sometimes sovereign) entities that have come together because they perceive potential benefits from cooperating. Even when a putative leader exists, their differing traditions, organizational and national cultures, goal structures, priorities, and processes ensure that the leader engages much more in developing shared understanding of the problem and ensuring appropriate collaboration than providing direct guidance, direction, or orders. Hence, there is no “commander” in an endeavor.

Another distinction between endeavors and other types of collectives is the set of dependencies and interdependencies involved in an endeavor. No single actor or set of actors within an endeavor is capable of achieving its relevant goals without appropriate activities and behaviors by other members. In some cases the more powerful actors within the endeavor bring the bulk of the resources and might be capable of achieving their short-term goals independently, but either issues of efficiency (not wanting to expend all the resources needed for this purpose), a sense that temporary gains would be offset by longer term factors unless the larger community participates, “buys in” and endorses the effort, or other considerations, such as ensuring perceptions the actions taken are seen as legitimate across the community, result in the decision to form an endeavor.

The actors within an endeavor may have a variety of different relationships with one another and may be working toward somewhat different goals or purposes. Indeed, their ability to work in concert may depend on the fact that their goals and objectives, while not identical, are not mutually exclusive. The endeavor should also be understood to extend to include actors whose behaviors only coincidentally support the goals of the endeavor. Such actors are less reliable partners than those who have chosen to work together, but they may nevertheless play useful roles under circumstances where their independently derived behaviors help create the conditions necessary for success.

Endeavors have a purpose or set of related purposes. They seek to have their members and the other relevant entities synchronize their efforts—arrange them purposefully in time and space—in order to generate effects consistent with those purposes. The degree of coupling between their efforts is voluntary. Members of an endeavor can simply decide to deconflict their efforts in space, time, and/or function. This was the classic approach taken by military organizations during the Industrial Age and in interagency efforts such as Katrina relief. Where there is little need for synergy, this approach can work. However, in the effects space required for twenty-first century endeavors, both military- and civilian-led, where success requires coherent results across the political, military, economic, social, and informational arenas, such deconfliction is inherently inadequate (NATO 2002, 92-93).

How Do Endeavors Work?

Endeavors are based on (a) goal alignment (to what extent are the actors in the endeavor able to agree on their purposes), (b) the capability of the endeavor to mobilize the relevant resources of those actors (not just what resources do they have, but to what extent are they willing to commit those resources to the endeavor), and (c) the capacity of the endeavor to establish appropriate arrangements between and among them and synchronize the efforts of the relevant actors in order to bring their resources to bear efficiently and effectively to support of the goals of the endeavor.

However, forming an endeavor does not guarantee success. Endeavors typically form when the actors are faced with a meaningful challenge. There is no guarantee that the actors have enough resources, the relevant knowledge (experience or skills), will power, or capacity to synchronize their efforts or to generate the desired effects. However, as the endeavor forms and begins to act, the parties to it obviously believe either (a) that they are capable of dealing with the challenge or (b) that they have no choice but to try to deal with it. Indeed, massive efforts carried out over long periods of time, such as the U.S. War on Drugs, have often experienced mixed success because of the challenging situations they sought to impact and the limits of their ability to cooperate and accept interdependencies.

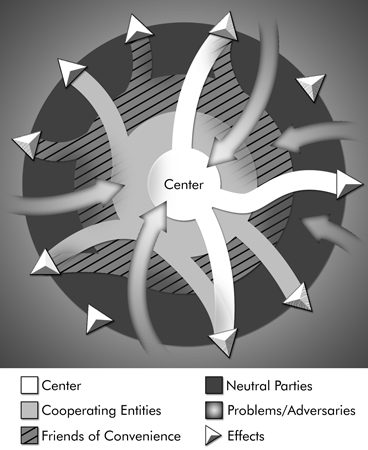

Goal Alignment

The first requirement for an endeavor is goal alignment, which is (by definition) never perfect because the actors are not identical, which implies that neither their interests nor the circumstances they perceive themselves to be in are identical. At the “Center” of the endeavor there may be a single actor or a relatively small set of actors whose goals are fully aligned or almost fully aligned and who have no significant competing goals that are meaningfully inconsistent with those of the endeavor or one another. At a minimum these actors must agree on the desired effects (or the objective functions) as a first step for the endeavor. Very often considerable time and effort are required before this set of core goals emerges and is agreed.

This Center is surrounded by actors who share this basic goal or set of goals, but who also perceive that they have other interests. Hence, these “Cooperating Actors” are not as fully committed or as reliable over time as those in the Center. If circumstances arise in which they perceive their other interests to become inconsistent with those of the endeavor, they may reduce their commitment or begin to behave in ways that impact the desired effects negatively. Hence, the Center must constantly monitor the Cooperating Actors and be aware of their current appreciation of the situation and future expectations about it.

FIGURE 2. Endeavor Structures & Patterns of Interactions

Beyond the Cooperating Actors lie those entities whose behaviors benefit the endeavor, but are based on goal structures different from those of the Center or the endeavor as a whole. For example, one warlord in Afghanistan may provide information about the illegal drug smuggling of another warlord so that coalition forces can take actions that will reduce the competition in the drug market. While these “Friends of Convenience” may be very important to endeavor success, they will be unreliable partners over time and across functional arenas. Here, again, the Center must maintain strong awareness of the real and perceived interests of these actors and the circumstances they perceive that might impact those interests.

Beyond the Friends of Convenience lie those actors who are indifferent to the goals of the endeavor, but are not opposed to them in any important way. The behaviors of these “Neutral Parties” may, however, be important for success. First, if common interests can be identified and agreed, the Neutral Parties may become Friends of Convenience or even Cooperating Actors. Secondly, these Neutral Parties are often part, even a major part, of the larger operating environment the endeavor is seeking to impact. In many endeavors, such as peace operations or stability and reconstruction efforts, the general population may be among the Neutral Parties. The often cited “battle for hearts and minds” focuses on this group.

Finally, endeavors are faced with Adversaries or Problems—those situations of actors they are seeking to effect. These can be states of nature (earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, or other natural disasters) and their aftermaths, which include refugee populations, diseases, or disgruntled groups critical of the responses to the disaster. Adversaries can also be nations, sub-national actors, or other political, social, or military groups, networks, or organizations (for example, drug lords) whose goals are inconsistent with those of the endeavor.

In all cases, these Adversaries and Problems are dynamic, not static. Where they are states of nature, they will change naturally as a result of the passage of time and alterations of their contexts. For example, storms beget floods, which create refugees, who are threatened by disease, hunger, and exposure. Where human adversaries are involved they should also be expected to learn over time and alter their behaviors to gain or maintain advantage.

Note also, as Figure 2 illustrates:

- The Center will have some ability to directly impact the adversary and to influence movement across the boundaries, but the endeavor can also be successful because of the effects generated by Cooperating Entities, Friends of Convenience, and Neutral Parties. These other actors often have more direct linkages and stronger interfaces with the Adversaries or the Problems.

- The “wise” endeavor works through all the assets available, reducing the burden on the Center and using the perceived self-interests and behaviors of all the actors (including the Adversaries and Problems) to its advantage.

- The Adversaries and Problems also impact the members of the endeavor, whether deliberately (as with an intelligent Adversary) or from natural changes that alter resource availability or the interests of the parties to the endeavor.

All actors are capable of changing roles over time or playing different roles when different issues are paramount. Hence, the boundaries between the types of actors are permeable. Managing the composition of the endeavor and the roles the different actors play over time and across function is an important part of making an endeavor work. Maintaining awareness of the posture of every significant actor is also an important issue.

Mobilization (Commitment or Will and Resource Commitment)

Each of the actors associated with an endeavor brings some relevant capabilities: knowledge, skills, experience, material resources, legitimacy, etc. These are their potential contributions to the endeavor. However, except in extreme cases (where the very existence of an actor is threatened), the willingness to contribute these capabilities will be limited. Typically each actor will want the others to carry as much of the burden as possible. Some deductions can be made from the existence and structure of the endeavor.

- First, the endeavor would not have formed (and will fall apart) if the actors did not perceive it to be in their interest(s) to deal with the Problem or Adversary.

- Second, the commitment level will depend on (and in a sense is defined by) the role of each actor in the endeavor. Those at the Center presumably have the most to lose if the endeavor fails or collapses, while willingness to pay a heavy price for success will decrease as the actors’ roles move away from the Center.

- Mobilization is, therefore, an important capability (and skill) in developing and managing the endeavor. Getting actors to change their roles by moving toward the Center will help, but the actors are also free to move away and may do so in order to reduce their level of commitment if their interests are perceived as not served by or moving away from those of the endeavor, either because circumstances change or because the endeavor changes its goals.

- Establishing the goals for the endeavor presents a paradox. If they are focused very narrowly in order to garner large participation and minimize the demands on any one actor, the endeavor will not be ambitious—it will settle for a “lowest common denominator.” However, if the goals are broad and far reaching, it may be difficult to recruit broad support and participation.

Analysts are cautioned that the challenges of building and maintaining an endeavor cannot be reduced to a simple rational choice model in which each actor is presumed to make an explicit cost-benefit calculation about joining the endeavor, which goals to support, and how much to invest in it. Many of these decisions will be highly emotional, involving issues such as nationalism, religion, or (particularly in the case of NGOs and PVOs) self-definition. Moreover, some of the actors (e.g., nation states, sub-national groups) also have important obligations to constituencies that will impact their decisions and behaviors. Some of the sets of motivations may appear inconsistent because the interests of an actor involve multiple interests. Hence holistic, inductive reasoning is likely to dominate many actors rather than deliberative calculations. This does not mean that analysis is impossible or unimportant. However, it does mean that in-depth knowledge, including cultural awareness, must be factored into the process.

Bringing Assets to Bear

While mobilization will decide what relevant resources are available, the actors in an endeavor will also make important decisions about how to deal with one another and how to synchronize their efforts. This area starts with the core questions of composition (who is involved) and structure. However, the underlying issues are the same ones we have earlier identified as the C2 Approach Space: (a) the allocation of decision rights, (b) the patterns of interaction between and among the actors, and (c) the distribution of information (Alberts and Hayes 2007, 169). From these factors it makes sense to assess the level of maturity available to the endeavor for each of its major activities. Those maturity levels cover considerable ground.

- Conflicted, in which the actors efforts are disjointed and interfere with one another (the least mature)

- Deconflicted, where the actors have divided their efforts over space, time or function, which means they can operate independently but cannot achieve synergies across those boundaries

- Coordinated, in which the actors have selected a few functional areas in which they work together

- Collaborative, in which the actors deliberately work together for a common purpose across much of the problem space

- Agile, in which a variety of C2 approaches are applied across the problem space based on which approach is best for the specific parties and the issues they are working (Alberts and Hayes 2007, 170-177; Alberts and Moffat 2006)

The most important consequence of these arrangements and practices is bringing the available resources into play in ways that matter. Very often the organizational structures and substructures form around functional activities, though the effects based world of the twenty-first century often requires cross-functional groupings for effectiveness. For example, delivery of food, water, shelter, and medicine to refugee populations can often be done more efficiently if the efforts are coordinated, despite the fact that they may be conducted by a variety of actors, each with specialized charters, expertise, and equipment. In many cases these deliveries also require support from military or police assets in order to provide security.

The structure of the endeavor will almost always have both a formal and an informal form. Even an “edge” endeavor (Alberts and Hayes 2003, 173) can be described as a structure to differentiate it from other types of entities. While formal structures are important, particularly during the formulation stages of an enterprise, they tend to morph into informal structures as actions “on the ground” force the actors to behave over time. Hence, the key organizational issues are those dealing with an informal organization: who actually participates and how do they organize their efforts to ensure they are synchronized and synergistic across the effects space of interest?

What Makes Endeavors Successful?

This is not primarily an article about how to create and manage a successful enterprise. That is a much larger topic and requires a detailed understanding of the purpose(s) being pursued and the context within which the endeavor is operating. However, we do know some general, quite abstract conditions that must be created for an endeavor to form and perform over time. These include:

- Trust between and among the actors, regardless of their roles in the endeavor

- Perceptions of competence

- Interoperability (technical, semantic, and willingness to share information and knowledge)

- Shared awareness (situation characterization)

- Shared understanding (cause and effect and temporal dynamics)

- Collaboration about purposes, decisions, planning, and execution

These factors have been dealt with in some depth elsewhere (Alberts and Hayes 2003; Alberts and Hayes 2007; Smith 2002; Smith 2006) and need not be belabored here, but the capacity of an endeavor depends critically on establishing and maintaining them over time.

Relevant Metrics

We previously have dealt with the issue of metrics related to command and control issues in a number of contexts (NATO 2002; Alberts and Hayes 2005; Alberts et al. 2002; Office of Force Transformation 2003; Alberts and Hayes 2003; Alberts et al. 2001; Alberts and Moffat 2006). Interestingly, changing the language from force to endeavor requires very little alternation in the approaches to measurement and metrics. Endeavors are collective entities that adopt C2 approaches and must deal with the same issues we raised more than a decade ago in Command Arrangements for Peace Operations (2005).

However, there are at least three measurement challenges implied in shifting from studying forces to studying endeavors.

First, generating an operational definition for an endeavor and applying it to enough cases to ensure its validity, reliability, and credibility is an essential step. This process has been initiated both in this article and in Planning: Complex Endeavors (2007). However, research on case studies will be essential before this issue can be seen as laid to rest. Most particularly, deciding where the boundaries lie for particular cases will be challenging. To take a simple example, are the efforts to create a stable and prosperous Afghanistan a single endeavor or a set of geographically or functionally distinct endeavors? The term endeavor may prove to be the label for a particular type of collective enterprise or system, in which case the boundaries can be established by analysts based on the purpose of their work. However, that is but one possible outcome of a discussion that has only just begun.

Second, analysis of endeavors will require new measurement focused on goal alignment. How much alignment is needed to define the Center of an endeavor? How will those who are Cooperating Entities be recognized as different from the Friends of Convenience? Each layer of an endeavor will need an operational definition and each definition will need to be tested for validity, reliability, and credibility. Like the definition of an endeavor, these definitions can only be tested by application. Indeed, one very healthy development might be the creation of a database, or better yet a knowledge base, of recent and current endeavors. Such a project would both ensure progress on these key measurement issues and also provide an important resource for research into the dynamics of endeavors and the conditions necessary to make them effective.

Third, the importance of goal alignment and the fact that changing circumstances can be expected to alter goal alignment among the actors implies a new emphasis on some aspects of the information, awareness, and sensemaking needed by those at the Center of an endeavor. Complete information and awareness must be extended to emphasize the actors’ perceptions of their interests and those circumstances that determine or condition those interests. In a sense, shaping the operating environment requires understanding the capabilities and willingness of potential partners in all layers of the endeavor. Hence, new metrics that allow assessment of goal alignment and knowledge of the dynamic factors that drive it will be needed.

Conclusion

A wide variety of the national security challenges facing the U.S. and the international community today are multi-dimensional, dynamic, and beyond the capacity of any one state or actor to meet. Network enabled and effects based approaches are hypothesized to offer significant advantages over traditional approaches to these problems, which require cooperation among a wide variety of entities. However, the term force, which has been widely used to describe the collectives created to deal with large problems and dangerous adversaries, implies a unitary structure and military orientation that are both incorrect and misleading. The term endeavor is much more accurate and better suited for describing and analyzing these collective efforts.

References

- Alberts, David S., and James Moffat. 2006. Maturity levels for NATO NEC command. Farnborough: DSTL.

- Alberts, David S., and Richard E. Hayes. 2003. Power to the edge. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., and Richard E. Hayes. 2005. Campaigns of experimentation. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., and Richard E. Hayes. 2005. Command arrangements for peace operations. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., and Richard E. Hayes. 2006. Understanding command and control. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., and Richard E. Hayes. 2007. Planning: Complex endeavors. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., John J. Gartska, and Frederick P. Stein. 1999. Network centric warfare. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., Richard E. Hayes, Daniel T. Maxwell, David T. Signori, and Dennis K. Leedom. 2002. Code of best practice for experimentation. Washington: CCRP.

- Alberts, David S., Richard E. Hayes, John J. Garstka, and David T. Signori. 2001. Understanding information age warfare. Washington: CCRP.

- Department of Defense. 2001. Network centric warfare Department of Defense report to Congress. Washington.

http://www.defenselink.mil/cio-nii/docs/pt2_ncw_main.pdf (accessed April 2007)

- Department of Defense. 2006. The quadrennial defense review report. Washington.

http://www.defenselink.mil/qdr/report/Report20060203.pdf (accessed May 2007)

- NATO SAS-026. 2002. Code of best practice for C2 assessment. Washington: CCRP.

- Office of Force Transformation. 2003. Network centric operations conceptual framework version 1.0. Washington: EBR.

- PBS Frontline. Thirty years of America’s drug war.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/cron/ (accessed April 2007)

- Pincus, Walter. 2007. U.S. Africa Command brings new concerns. Washington Post, May 28, A13.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/05/27/AR2007052700978.html (accessed May 2007)

- Ricks, Thomas E. 2006. Fiasco: The American military adventure in Iraq. New York: Penguin.

- Smith, Edward A. 2002. Effects based operations. Washington: CCRP.

- Smith, Edward A. 2006. Complexity, networking, and effects-based approaches to operations. Washington: CCRP.

- The White House. 2002. The national security strategy of the United States of America. Washington.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/nss.pdf (accessed May 2007)

- The White House. 2006. The federal response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons learned. Washington.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/reports/katrina-lessons-learned.pdf (accessed May 2007)

- U.S. House of Representatives. 2006. A failure of initiative. Washington: GPO.

http://www.gpoaccess.gov/katrinareport/fullreport.pdf (accessed May 2007)